The first round of negotiations between the United States and Iran took place on February 6 in Oman, with further rounds expected to follow. The talks are being conducted indirectly through Omani mediators. These negotiations are unfolding under visible military pressure. The United States has reinforced its military posture in the region by deploying carrier strike groups into the Gulf as part of a broader form of “gunboat diplomacy.” Regional actors, including Turkey, are concerned that failure in the negotiations could lead to war.

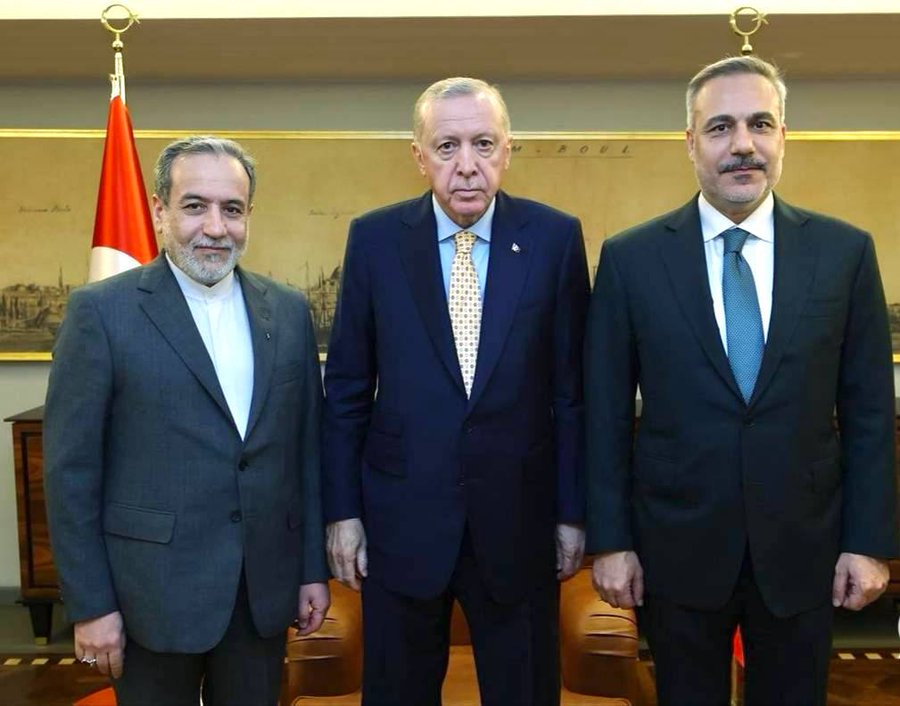

Ankara has repeatedly made clear that it opposes a military intervention against Iran. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated again on February 5: “We are doing everything to prevent these tensions between the United States and Iran from driving the region into a new conflict and chaos. We clearly expressed our opposition to a military intervention in Iran.” To this end, the Turkish government has also formed a sort of ad hoc alignment with regional countries to lobby the Trump administration against war.

Why Turkey Is Pushing Against War

The main reason Turkey does not want a war against Iran is the fear of regional collapse. Iran’s regional influence has already taken hits in the aftermath of the war in Gaza and the 12-day war, and many governments in the region worry that further military pressure could push Iran into a downward spiral that no one can fully control. The U.S. invasion of Iraq is still fresh in memory.

For Turkey, this is also a direct security issue. From Ankara’s perspective, a power vacuum in Iran would almost certainly create room for groups that Turkey already considers major security threats. During recent protests inside Iran, Turkish intelligence reportedly warned Iranian authorities that PJAK, the Iranian branch of the PKK, was attempting to exploit unrest conditions.

Economic factors also shape Turkey’s position. Despite sanctions, Iran remains an important energy partner for Turkey. Iran accounted for roughly 14% of Turkey’s natural gas imports in recent years. Beyond direct imports, Iran also plays a key transit role in Turkey’s diversification strategy. Turkey receives Turkmen natural gas through swap arrangements that rely on Iranian territory and infrastructure. This system allows Turkmen gas to reach Turkey using Iranian pipeline networks. Any major instability inside Iran would therefore threaten Turkey’s energy security.

At a broader strategic level, Turkish policymakers, similar to some Gulf governments, are more comfortable dealing with an Iran that is constrained and partially isolated than with a country that is fully reintegrated into the Western system and able to fully use its vast economic and resource potential. Historically, when Iran was closely aligned with Western powers before the 1979 revolution, it functioned as a dominant regional actor capable of imposing its will when necessary. The nuclear program itself was launched during that period with U.S. assistance under the Shah.

A Regional Framework for Limiting Iran’s Capabilities

In this regard, Turkey and Arab states do not support an unconstrained Iranian nuclear trajectory. Their preferred outcome is a negotiated framework that limits enrichment to levels that cannot easily be weaponized while preserving regional stability. Qatar, Turkey, and Egypt have already proposed a framework under which Iran would halt uranium enrichment entirely for three years and then cap it below 1.5%, while transferring its current stockpile of highly enriched uranium — including roughly 440 kg enriched to 60% — to a third country. The proposal also includes limits on ballistic missile use, restrictions on arming regional allies, and a possible U.S.–Iran non-aggression agreement.

Tehran appears willing to negotiate technical limits but remains unwilling to completely abandon enrichment or ballistic missile capabilities. Iran is also likely trying to stretch the negotiation timeline, using extended technical discussions to reduce immediate pressure. The Trump administration, by contrast, has little patience for prolonged technical negotiations and prefers faster outcomes.

The Cost of a Failed Negotiation

If negotiations fail, military options remain on the table for the Trump administration. These could range from targeted strikes on Iranian military or Revolutionary Guard infrastructure to symbolic operations designed to demonstrate strength without triggering full-scale war, or even a Venezuela-style decapitation attempt.

Despite their differences, Ankara and Tehran have decades of experience managing their rivalry. Turkish policymakers have developed a good understanding of how Iranian governments operate and how Tehran approaches negotiations.

For Turkey, the strategic goal is therefore clear: prevent escalation and reduce nuclear and missile risks without triggering wider regional instability. From Ankara’s perspective, further pressure on Iran risks deepening the current shift in regional power dynamics, at a time when Israel has expanded its influence.