- Turkey’s Syria policy did not simply shift from ideology to realism. It reflected a change in how Ankara understood the region. Turkey moved from expecting regional transformation to prioritizing stability.

- Between 2011 and 2024, Turkey backed efforts to undermine the Assad regime. Since late 2024, it has focused on consolidating and stabilizing the Syrian state under President Sharaa.

- Turkey’s policy in northern Syria is driven by its determination to prevent the survival of a PKK-linked armed structure along its border. This policy defines how Ankara deals with the SDF and how it coordinates with Damascus. Developments in Syria will continue to shape Turkey’s regional foreign policy, which remains primarily driven by security considerations.

- Turkey prioritizes state consolidation and stability in Syria and shows little interest in pushing political liberalization.

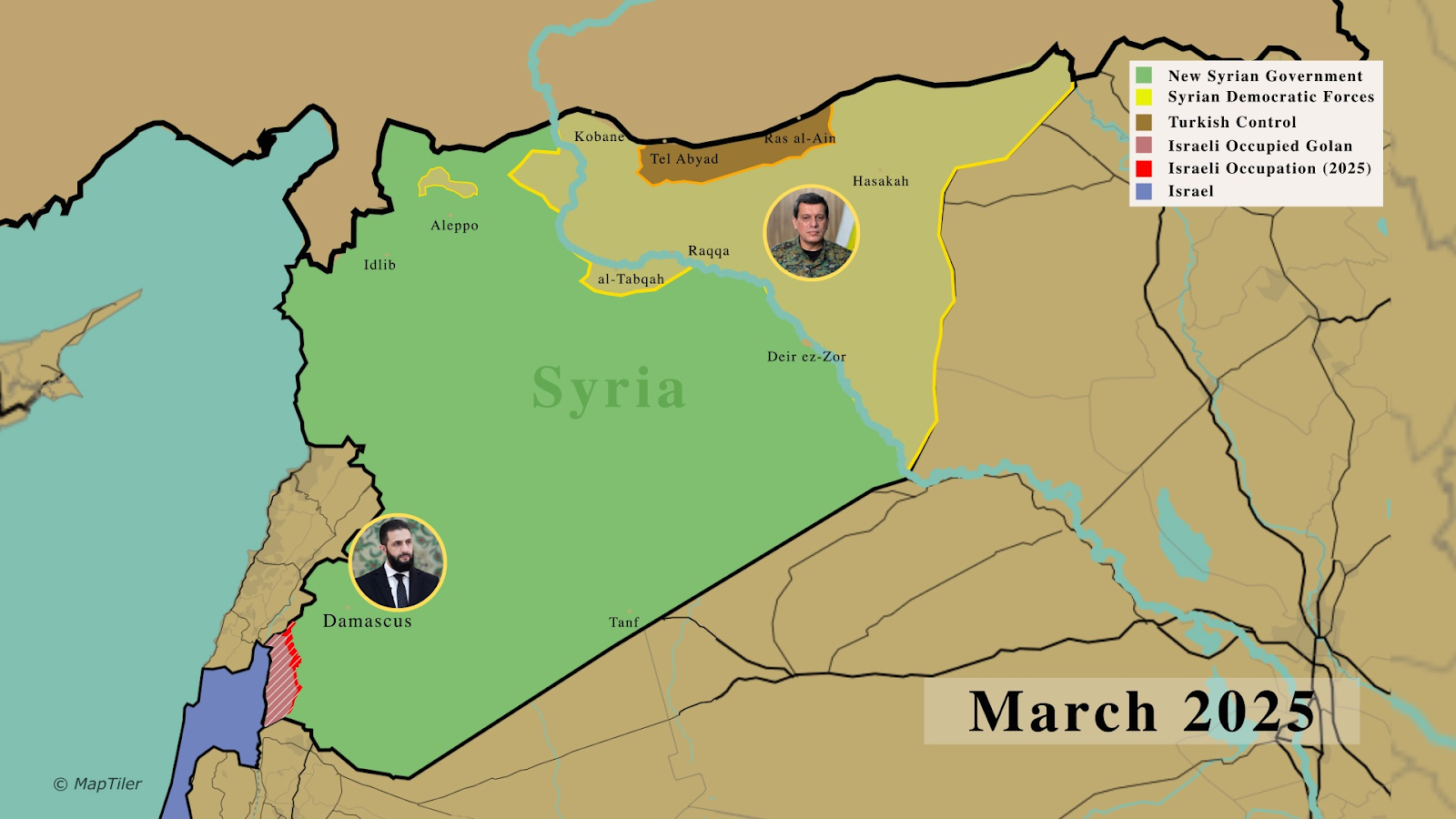

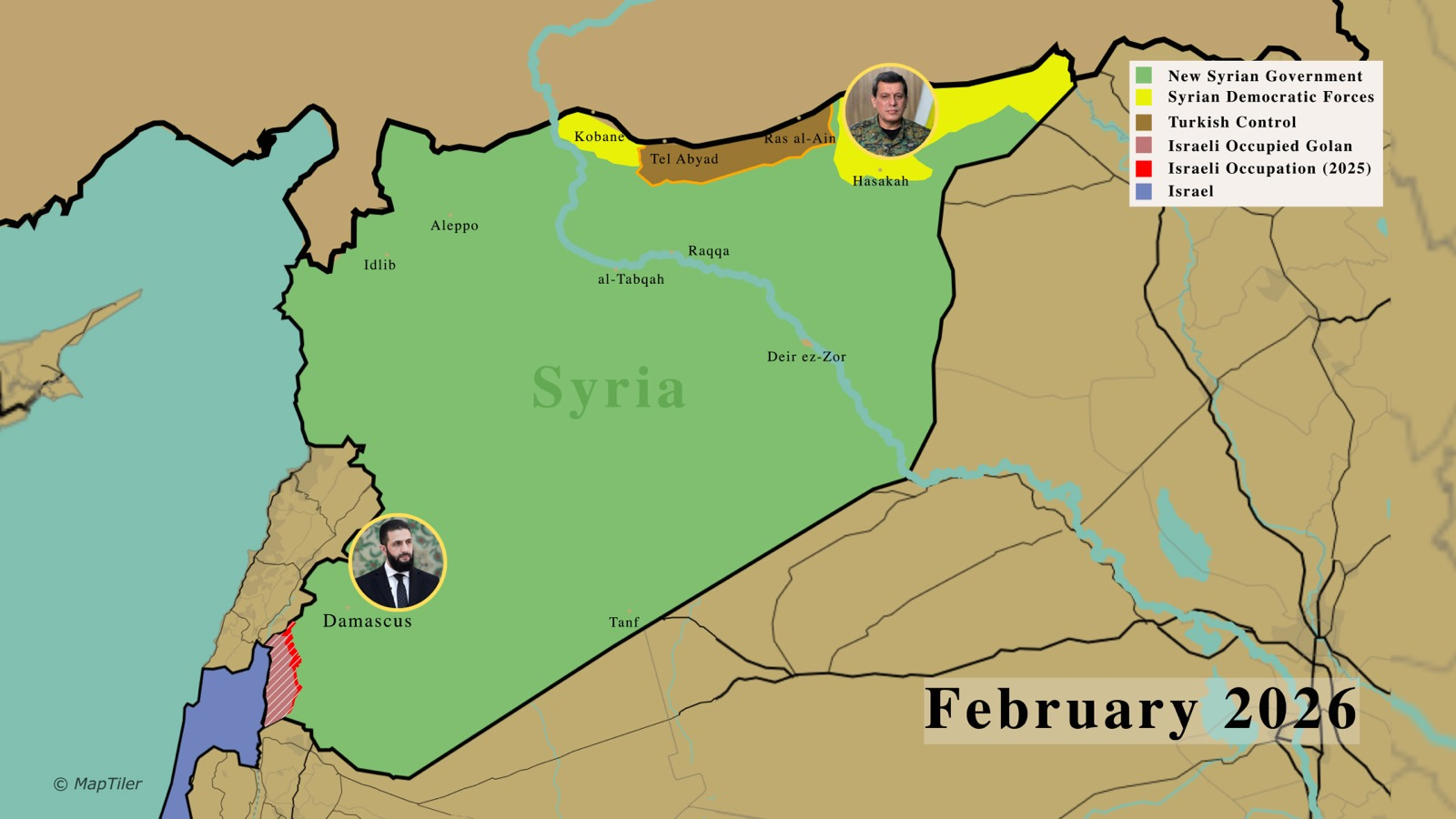

- The January 2026 developments marked a decisive shift in the balance of power in Syria. The SDF lost the ability to negotiate from a position of strength. The project of autonomous governance in northeastern Syria largely has been severely undermined.

-Turkey sees Syria’s economic recovery as essential for the survival of the new authorities in Damascus. The path ahead depends on investment in energy, agriculture, and transport infrastructure, which could allow the economy to gradually recover.

- Turkish–American relations over Syria moved through three phases: early alignment around political change (2011–2014), prolonged tension driven by diverging priorities and the U.S. partnership with the YPG (2014–2024), and post-Assad pragmatic management of disputes under a new balance of power.

- Turkey and Israel are developing a structural rivalry over Syria because they want different outcomes: Turkey favors a stable unified Syrian state, while Israel prioritizes limiting Syrian state power.

For more than a decade, Ankara worked to undermine the Assad regime, arm the opposition, and shield it from a certain defeat. Under Turkish military and diplomatic cover, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) survived offensives, consolidated control in the northwest, and eventually became the driving force behind the rapid collapse of the old regime.

Today, the same Turkish government that played a major role in overthrowing Assad regime presents itself as a supporter of stability in Damascus. In other words, Turkey’s policy has shifted from regime change to regime consolidation in Syria. Ankara now seeks to boost its influence over the new leadership and prevent outcomes that could undermine its position in the region.

This report analyzes Turkey’s vision for Syria following the fall of the Assad family and the rise of the HTS under the leadership of Ahmad al-Sharaa. In this regard, it focuses on the foreign actors that, alongside Turkey, now have the greatest ability to shape Syria’s future: namely the United States and Israel. Turkey is deeply invested in the survival and consolidation of the new authorities in Damascus. The United States remains the key external power when it comes to international legitimacy, sanctions policy, and the broader security environment. Israel, meanwhile, has become one of the most active military actors in Syria and is pursuing security objectives that often collide with Turkey’s preference for a stable and unified Syrian state.

We initially considered including Russia and Iran as central pillars of the analysis. However, since the fall of Assad, their ability to shape outcomes on the ground — or even to disrupt them — has been significantly reduced. Both countries have lost critical assets and influence inside Syria. At the same time, each is heavily absorbed by its own pressures. Russia remains tied down by the war in Ukraine, while Iran has already fought a direct confrontation with Israel and faces the possibility of another escalation involving the United States.

Some sections of this report build on earlier analyses that were previously published at instituDE.org. These chapters have been updated and expanded to reflect the rapidly evolving balance of power on the ground in Syria.

The report first examines the role of ideas in Turkey’s Syria policy and how Ankara’s understanding of the region has evolved over time. It then examines the consequences of the SDF’s miscalculations and how they reshaped the balance between Damascus, Ankara, and local actors in northeastern Syria. The report next analyzes Turkey’s security approach in northern Syria.

It then traces the evolution of Turkish–American relations during the Syrian conflict. The report also examines how developments in Syria, alongside the war in Gaza, are deepening tensions between Turkey and Israel and reinforcing their competing approaches to Syria. It then turns to Syria’s economic reality after more than a decade of war, including reconstruction needs, sanctions, and the fragile early phase of recovery. The report concludes by returning to Turkey’s vision for the new Syria and the constraints that will shape how far Ankara can influence what comes next.

Haşim Tekineş

Turkey’s Syria policy is often portrayed as a case of foreign policy failure driven by ideology. According to this view, Ankara abandoned realism in favor of Islamist enthusiasm during the Arab Spring and later returned to pragmatism after paying significant political and strategic costs. While this narrative highlights an important shift, it relies on a simplified understanding of the relationship between ideas and foreign policy. It assumes that ideology merely distorts an otherwise objective reading of material realities and that policy change occurs once decision-makers rediscover realism.

This article adopts a different perspective. It argues that Turkey’s response to the Syrian civil war reflects an ideological transformation rather than a simple return to realism. Focusing on the period between 2011 and 2025, it examines how Ankara’s understanding of itself, its rivals, and the Middle East evolved during the conflict. The article explains this transformation through three interconnected dimensions: the ideas held by decision-makers, the changing influence of transnational Islamist networks, and processes of institutionalization.

2011 and 2025: Two Moments in Turkey’s Syria Policy

The change in Turkey’s Syria policy (and foreign policy more broadly) is usually explained as a shift from an ideological approach to foreign policy realism. In this view, ideas and ideologies are seen as obstacles that distort an objective reading of reality and, therefore, of national interests. However, the material environment does not speak for itself. It requires interpretation, and this act of interpretation shapes how causality, threats, and opportunities are understood.

Having said that, ideas are not independent phenomena.1 They operate in constant interaction with the material environment.2 As long as they help explain complexity and produce positive outcomes, they remain influential. When they fail, alternative ideas gradually replace them. This is what Turkey experienced during the Syrian civil war.

In 2011, the Turkish government viewed Turkey as a regional leader with the potential to shape the Middle East in its own way. During the 2000s, the country experienced a degree of democratic and economic improvement under an Islamist, culturally conservative government. Although exporting the “Turkish model” was not an explicit policy objective, Ankara believed that its interests were best served by the democratization of the region.

In fact, from Ankara’s point of view, democratization meant returning to normal in the Middle East. The uprisings were seen not merely as political revolts but as a return to the region’s authentic social and political foundations, which had been distorted by authoritarian and secular regimes.

Contrary to the popular belief, for the Turkish government, the winners of the democratization did not have to be Islamist. Ankara believed that, whether secular or Islamist, new democratic actors would be closer to Turkey. Why would a democratically elected secular government not cooperate with Ankara? At the same time, like many other governments, Turkey expected democratization to strengthen Islamist movements in the region — groups that were assumed to share ideological and cultural affinities with Ankara. Enjoying the best of both worlds, Erdoğan and Davutoğlu could be champions of democracy and Islam.

The Turkish government also overestimated the strength of revisionist actors such as Islamists and liberals. Because political systems in the Middle East were largely closed, it was difficult to observe internal social and political dynamics. Assessments of power balances therefore relied more on personal impressions and public enthusiasm than on systematic data such as surveys.

Still, it was not a belief in the historical inevitability of change that shaped Ankara’s Syria policy. Internal deliberations show that decision-makers were concerned that the scenarios seen in Libya or Egypt might not be repeated in Syria. They were, in fact, more cautious about Assad’s future. Nevertheless, they concluded that Turkey’s interests ultimately lay in political change, despite the strong economic, diplomatic, and political ties it had developed with Damascus.

Turkey is now a different country. Today, far from becoming more democratic, Erdoğan has consolidated power and turned into an authoritarian leader. Turkey no longer expects (or seeks) a major regional transformation that would align with its interests. Instead, it is possible to argue that Ankara now prefers stability over change. Stability, in its view, allows the government to manage national security challenges more effectively and to maximize economic benefits.

Turkey has also learned to maintain relations with both Islamist and anti-Islamist actors. It now approaches regional crises not as a patron of religious allies, but as a pragmatic actor focused on profit and security. As a result, Ankara has become more flexible in its alliances.

Taken together, these developments point to a fundamental shift in the Turkish government’s assumptions about itself, its rivals, and the broader region.

Ideas and Their Owners

Yet, how does one way of understanding the world overcome others? In other words, how do ideas gain power? One major way is through the power of their carriers. If the owner of an idea is in a decision-making position, this gives them actual impact on the ground.

One such person was Ahmet Davutoğlu. Since AKP’s early days in power, Davutoğlu had become an influential figure in foreign affairs. Davutoğlu first served as foreign policy advisor, then foreign minister, and finally as prime minister. Davutoğlu was the one who drew ideological framework of Turkey’s foreign policy until 2016.3 It is hard to say he offered a sound Islamist strategy with clearly defined goals. Yet, he offered a vision and assumptions to understand the region. Moreover, he was in a position to implement his policies and to change bureaucratic practices.

Second, it is possible to argue that Davutoğlu was a more devoted Islamist than Erdoğan who was more pragmatist. During his political career, Erdoğan has many times proved that he could easily change track and break his words. However, Davutoğlu is more inflexible in such changes. With his strong self-perception of intellectualism and idea maker, he attaches more importance to ideological consistency. In other words, if Davutoğlu is in a decision-making position today, Turkey could act more triumphant in Syria and more bellicose with Israel.

In the Turkish case, Erdoğan and the AKP leadership have remained in power throughout this period. Yet, the removal of Ahmet Davutoğlu from government has been an important dynamic in Turkey’s turning away from Islamism in foreign policy. Indeed, when Erdoğan removed Davutoğlu from the premiership, the new motto was “increasing the number of friends and decreasing the enemies” – which signaled dissatisfaction with the costs of his foreign policy.4

Transnational Islamist Networks and Their Declining Influence

Transnational networks are another way for ideas to shape reality.5 Such networks' contacts in decision making mechanisms of a country could influence its decisions, by shaping understanding of reality, perceptions of interests. Indeed, the AKP's closeness with the Muslim brotherhood and similar groups influenced its foreign policy at the beginning of Arab Spring.

Since the 1950s, Turkey’s political Islamists had started to know more about the Brotherhood and other Islamist groups around the world. Erdoğan, Davutoğlu, and other leading AKP figures had decades-old contacts from those circles. Those networks provided strategic input to the decision makers and shaped Ankara’s policies.

Erdoğan’s rhetoric during and after the 2013 coup in Egypt illustrates this influence. Muslim Brotherhood symbols and figures featured prominently in his speeches. The four-finger “Rabia” hand sign became a powerful symbol of solidarity with the Brotherhood and opposition to the Sisi regime.6

Over time, however, the meaning of these symbols changed.7 Erdoğan later redefined the Rabia sign as representing nationalist principles rather than Brotherhood suffering. This shift reflected a deliberate distancing from transnational Islamist movements without openly disavowing them.

Turkey remains a sanctuary for Islamist figures fleeing repression in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Yemen. Yet Ankara has shown that it is not an unconditional partner. In some cases, Turkey has handed over Islamist figures to Egypt, signaling that ideological solidarity no longer overrides diplomatic calculations.8

At the same time, Turkey’s informational and economic networks have diversified.9 Ankara now maintains extensive contacts with non-Islamist actors and business elites across the region. These interactions have reshaped Turkish perceptions of regional politics and reduced the influence of ideologically homogeneous networks on decision-making.

Institutionalization of Ideas

As states invest in certain ideas in critical turning points, such as Arab Spring, those ideas institutionalize and become harder to turn back.10 They took concrete shapes in bureaucratic practices and government discourse. Since investment grows in time, it becomes increasingly harder to turn back from those ideas despite their failure or increasing costs.

In the first half of the 2010s, Ankara remained committed to its course despite rising costs. İbrahim Kalın, then Erdoğan’s chief advisor, famously described Turkey’s regional isolation as “precious loneliness.”11 This phrase captured the belief that moral correctness justified diplomatic isolation.

The persistence of this approach was partly due to the institutionalization of ideas. By the time doubts emerged, Turkey had already cut ties with Assad, damaged relations with key regional actors, and invested heavily in the Syrian opposition. Ankara’s support extended to armed groups, including al-Qaeda–affiliated factions, and possibly even the ISIS. These commitments created path dependencies that made rapid policy reversal difficult.

Material and geopolitical constraints gradually undermined Ankara’s ideological ambitions. Two developments were particularly decisive. First, the United States’ partnership with the YPG in Syria posed a direct threat to Turkey’s national security. Second, Russia’s military intervention in 2015 shattered Ankara’s hopes of toppling Assad through opposition forces.

These developments forced a reassessment in Ankara. Erdoğan began to signal, for the first time, that Assad might remain in power, at least temporarily.12 This marked an important change in mindset. Instead of an expectation of a change, Turkey’s perception of national threat grew in time.

Turkey’s subsequent normalization efforts reflected this shift. Ankara repaired relations with Russia after the 2015 jet crisis, re-engaged with Israel, and later sought rapprochement with Egypt. After 2016, Turkey even provided diplomatic assistance that indirectly helped Russia and the Assad regime reclaim opposition-held territories. These policies would have been unthinkable during the peak of Turkey’s Islamist enthusiasm.

The transition, however, was not linear. Events such as the Qatar crisis in 2017, the Khashoggi killing in 2018, and rivalry with the UAE temporarily revived Islamist rhetoric in Turkish foreign policy. Yet even in these cases, Ankara ultimately opted for pragmatic outcomes. By late 2020, Turkey normalized relations with both the UAE and Saudi Arabia, followed later by reconciliation with Egypt. Each episode ended not with ideological escalation but with compromise.

Ideas and Adjustment in Turkey’s Syria Policy

The comparison between Turkey’s Syria policy in 2011 and 2025 reveals a fundamental shift in how Ankara understood the region, power, and its own capacity to shape outcomes. Early in the conflict, Turkish decision-makers interpreted the Arab Spring as a historically corrective process that aligned moral legitimacy with strategic interest. This view sustained ambitious policies despite mounting costs and unfavorable developments. Over time, however, prolonged conflict, external intervention, and direct security threats undermined these assumptions and reduced the explanatory power of earlier ideas.

By the time Assad was overthrown, Ankara was no longer framing Syria as a site of regional transformation but as a problem requiring careful management. Islamist language persisted, yet it no longer defined policy expectations or alliance choices. Turkey’s foreign policy had become more flexible, transactional, and risk-averse, reflecting a new set of ideas about stability, threat, and influence.

Mustafa Enes Esen

The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) emerged as a dominant military and territorial actor in eastern Syria following the U.S.-led campaign against ISIS. Their control of large areas has created sustained tension with Turkey, which views the SDF as an extension of the PKK. Turkey’s opposition to an independent SDF military structure, alongside Damascus’s efforts to reassert authority in eastern Syria, has made the status of the YPG, the SDF’s military backbone, a central issue in the negotiations.

U.S. Military Backing and Territorial Control After ISIS

The rise of the Kurdish fighters in Syria is inseparable from the U.S.-led campaign against ISIS. When Washington intervened militarily in Syria in 2014, it recruited the PKK’s Syrian branch, YPG, as its primary local partner on the ground.14 Supported by extensive U.S. air power, YPG forces led ground operations against ISIS in eastern Syria, reportedly losing around 11,000 fighters.15 Following ISIS’s defeat, the YPG, took control of most of the territory previously held by the group, including areas along the Euphrates River that account for the bulk of Syria’s oil production.

The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), formed in 2015, is a multi-ethnic military coalition in which the YPG constitutes the main military component. During the Syrian civil war, the SDF avoided direct confrontation with the Assad regime. Instead, it pursued a policy of non-aggression and selective cooperation. This arrangement allowed the SDF to consolidate its territorial control. While regime forces retained enclaves within SDF-controlled territory, such as military bases in Hasakah,16 the SDF also maintained a presence in some neighborhoods of Aleppo that remained formally under regime authority.17 This coexistence was not necessarily the result of political alignment but of mutual convenience.

The SDF possessed heavy weaponry supplied by the United States and equipment seized from retreating regime forces. While the SDF claims to have around 100,000 fighters, the actual number of active combatants was lower.18 However, the YPG appeared to have trained a large pool of personnel and could retain a significant reserve capacity.

The arrangement collapsed with the fall of the Assad regime at the end of 2024. With the Assad regime’s authority gone, the SDF rushed to fill the power vacuum created by the regime’s withdrawal by moving into several towns around Deir ez Zor,19 while simultaneously facing the risk of encirclement west of the Euphrates by HTS and Turkish-backed armed groups. Following negotiations, the SDF withdrew its forces from west of the Euphrates, with the exception of a few neighborhoods in Aleppo, and transferred control of certain settlements in western areas around Deir ez Zor.

The March 10 Agreement Between Damascus and the SDF

The integration agreement signed on March 10, 2025, between the new Syrian government in Damascus and the SDF represented a significant but fragile compromise.20 The deal would place all civil and military institutions in northeastern Syria, including oil and gas facilities, under state authority, strengthening Damascus’s claim to sovereignty. However, the agreement deliberately avoided resolving the most contentious issue: the integration of the SDF’s armed wing, the YPG, into the Syrian army.

These questions were deferred to future negotiations, making implementation the central test of the deal. For Turkey, the agreement reduced the immediate likelihood of large-scale military operations in eastern Syria but failed to meet Ankara’s core demand: the dismantling of the YPG as an autonomous armed force.

Collapse of the March 10 Agreement

The chain of events that culminated in the collapse of the SDF lines did not begin with the fighting east of the Euphrates. It began earlier in January 2026 with talks held in Paris between Syria, the U.S., and Israel, where it was reiterated that territories west of the Euphrates were to fall under the authority of the Damascus government.21 What followed was not just escalation, but also the gradual implementation of these talks through the use of force on the ground.

The first concrete manifestation of this shift occurred in Aleppo. The SDF-held neighborhoods in the city were violently taken over between January 6 and 10. Following events in Aleppo city, pressure moved eastward.22 Between January 13 and 16, Syrian government forces launched an operation against the SDF around Deir Hafir and Maskana.23 These settlements were designated as military zones, access roads to Maskana were closed, and Syrian reinforcements were deployed from Latakia.24 Anticipating more intense fighting than in Aleppo, the SDF also reinforced the area with units from Hasakah, Shaddadi, and Qamishli.25 Damascus asserted that these reinforcements included PKK elements as well as former officers who had served in the Assad-era military.26

On January 16, in the face of the growing military build-up and the intervention of the U.S. military, the SDF began to withdraw from Deir Hafir and Maskana.27 Following the SDF’s withdrawal, the Syrian army launched a further operation to control areas west of the Euphrates on January 17.28 As it became more apparent that the SDF was unable to hold its positions and that the United States would not intervene to protect them, fighting ensued in other theaters.29

The next and final phase of the military operation unfolded east of the Euphrates. As Arab tribes began switching sides, Syrian government forces have been able to make quick gains.30 The SDF, which relied heavily on tribal cooperation to administer vast and sparsely populated areas, has begun losing positions almost simultaneously across multiple fronts. Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor have passed under Damascus’s control. Government forces have since reached the outskirts of Hasakah. This has not been a gradual erosion but a sudden loss of depth.

With the loss of Raqqa and much of Deir ez-Zor, the SDF also lost control of oil fields along the Euphrates.31 For the SDF, oil was the backbone of its economic model and its main source of independent revenue. Before the civil war, Syria produced roughly 400,000 barrels of oil per day, a figure that fell to around 40,000 barrels, which was once substantial for the SDF.32

From the March 10 Framework to January 30

This collapse has directly invalidated the tenets underpinning the March 10 agreement. That framework was negotiated at a moment when the SDF still believed it could negotiate from a position of relative strength. The idea of integrating SDF forces into the Syrian army while retaining their command structure, potentially through the formation of several organized units, was now gone for good.

The ceasefire agreement of January 18 redefined the framework for the reintegration of SDF-held areas into the Syrian state. SDF security personnel would join state institutions only on an individual basis, subject to vetting and reassignment, with no provision for collective integration. Control over border crossings, oil and gas facilities, and internal security would be transferred to Damascus. The agreement also called for the removal of non-Syrian PKK elements from Syrian territory.

Civil and administrative institutions in Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, and Hasakah were to be absorbed into the Syrian state.33 Perhaps most consequentially, responsibility for the fight against ISIS and for the detention of former ISIS members was handed over to the Syrian government. The ISIS issue was the SDF’s primary source of international legitimacy.

January 30 Agreement

The latest integration agreement between Damascus and the SDF on January 30 establishes a new framework for the integration of northeastern Syria into the authority of the central government.34 The deal reflects the balance of power created after the January operations and sets out the political, military, and administrative terms governing the relationship between the two sides.

Under the agreement, both Syrian government forces and SDF units are to withdraw from active front lines, reducing the risk of immediate confrontation. The SDF is granted limited political participation in the new administrative structure. This reportedly includes input into a small number of senior appointments, such as the governorship of Hasakah and the position of Deputy Minister of Defense.

On the military side, the agreement outlines a pathway for the integration of SDF fighters into the Syrian army. Current reporting suggests that integration could take place through the formation of three divisions composed largely of former SDF personnel. In this respect, the arrangement appears closer to the framework discussed in the March 10 agreement than to the harsher terms imposed after the January 18 ceasefire. However, the political and military balance has shifted significantly since early 2025, meaning that similar provisions now operate under far less favorable conditions for the SDF.

The agreement also includes provisions for the gradual transfer of control over territory and infrastructure to Damascus. Until the end of last year, the SDF controlled roughly one third of Syrian territory — around 50,000 square kilometers — including most of the country’s oil resources and a large share of its agricultural land. Following the January operations, this area was reduced to approximately 10,000 square kilometers. Under the new terms, remaining critical infrastructure, including oil facilities, electricity networks, water infrastructure, and key border crossings, will come under central government authority.

Important details remain contested. Some reports indicate that SDF fighters will be integrated individually into Syrian army units, which would effectively dissolve the SDF as a cohesive military structure. Other accounts suggest a more flexible arrangement that could allow elements of existing SDF formations to remain partially intact during the transition period. The final implementation will likely depend on the evolving balance of power and the level of external pressure on both sides.

The SDF’s Strategic Miscalculations

These outcomes were, to a significant extent, the product of a series of miscalculations by the SDF. One of the most consequential errors was its failure to correctly read the evolving regional and international environment. Expecting prolonged instability in western Syria, the SDF dragged its feet in implementing the March 10 agreement at a time when it still retained leverage. Meanwhile, the new leadership in Damascus consolidated control in the west, undermining the assumptions on which the SDF’s delaying strategy rested.

The SDF also misjudged the trajectory of regional alignment. Once Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar coalesced around Damascus, the Trump administration decided to give Sharaa a chance.35 Damascus, rather than the SDF, has emerged as Washington’s primary partner in Syria. The SDF failed to internalize the implications of this shift, continuing to operate on the assumption that its role east of the Euphrates was unshakeable.

Warnings pointing in this direction were repeatedly discounted by the SDF leadership as individual assessments, such as the clear statements of the U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of Turkey and Special Envoy for Syria, Tom Barrack, rather than as signals of a broader policy change.36 This misreading proved costly. The SDF’s territorial control had always been contingent on U.S. military backing. Once it became clear to the SDF that Washington would not actively obstruct Syrian government advances, it was already too late.

Moreover, the SDF was never a cohesive or uniform force. A substantial portion of its manpower consisted of Arab fighters embedded within tribal structures where loyalty is fluid. In such an environment, allegiance shifts quickly when incentives change. As Syrian government forces gained momentum and tribal defections accelerated, the collapse of the SDF became inevitable.

Mustafa Enes Esen

The SDF has formally disassociated itself from the PKK.38 Nonetheless, its cadre structure, ideological orientation, thousands of PKK members in its ranks, and the pervasive presence of Abdullah Ocalan’s imagery across SDF-controlled areas indicate continuity rather than rupture.39 This continuity has been decisive for the Turkish government. In this regard, Ankara does not distinguish between the PKK and the YPG, the military backbone of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and treats the SDF as a PKK-led entity operating along its southern border.

One of the primary drivers behind Turkey’s military interventions in Syria after 2016 was to prevent the territorial expansion and consolidation of the YPG following the defeat of ISIS. Despite objections from Russia, Iran, the Assad regime, and the Pentagon, Ankara treated the YPG’s growing control as a direct national security threat. Turkey expanded the areas under its control in northern Syria whenever conditions permitted, either through direct military operations or via proxy forces.

Ankara conducted four major cross-border operations aimed at disrupting YPG territorial continuity and providing shelter to armed opposition within Syria: Operation Euphrates Shield (2016), Operation Olive Branch (2018), Operation Peace Spring (2019), and Operation Spring Shield (2020). As Turkey lacked a UN Security Council mandate or the consent of the Assad regime, it justified these military interventions primarily on the basis of self-defense and counterterrorism, while also making secondary references to humanitarian concerns and UN-led political processes.40

After the fall of the Assad regime, Turkey coordinated closely with the Sharaa government on the SDF and continued to press the Trump administration for its dissolution within the Syrian army. By contrast, the SDF viewed its military capacity as the main guarantee of its political leverage and autonomy. Without an independent military structure, the Kurds would have had little chance to extract concessions from Damascus, and prospects for federalism or enhanced autonomy would have effectively disappeared.

For this reason, the SDF was unlikely to lay down its arms without firm external security guarantees. The talks between Damascus and the SDF postponed confrontation throughout 2025 but did not resolve the underlying conflict. These dynamics ultimately culminated in a new phase of conflict in January 2026, which resulted in the collapse of the SDF lines.

Ankara’s Reaction to the Recent Developments

The Turkish government is content with the collapse of the SDF. Erdoğan told Sharaa in a phone call on the day of the ceasefire agreement, January 18, that “the complete removal of terrorism from Syrian territory is necessary for both Syria and the entire region.”41 The first official statement of the Turkish Foreign Ministry welcomed the agreement and stated that “we hope that it will be fully understood by all groups and individuals in the country that the future of Syria is not through terrorism and division, but through solidarity and integration. Turkey will continue to support the anti-terrorism efforts of the Syrian Government.”42

According to Ankara, the agreement addresses Turkey’s long-standing security concerns in Syria.43 The removal of non-Syrian PKK elements from Syria and the departure of PKK-linked cadres strike at the core of Ankara’s objections to the SDF project. The withdrawal of heavy forces from Kobane and their replacement by local security units tied to the Syrian Ministry of Interior are also a positive development for Ankara.

On the other hand, the PKK’s 2025 announcement of its dissolution was primarily driven by a desire to safeguard its gains in Syria.44 This included the SDF’s establishment of a semi-independent entity with aspirations for future independence should regional dynamics align favorably. With those gains now being dismantled, the organization faces a strategic dilemma. How can it survive in this entanglement? The collapse of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in northeastern Syria, therefore, carries significant ramifications for Turkey’s ongoing “Terror-Free Turkey” peace process with the PKK.

The heavy setbacks suffered by the SDF in recent days now threaten to derail the Turkish solution process entirely, as PKK elements have openly implied that continued aggression against their Syrian counterparts could force a reevaluation of the ceasefire and negotiations. PKK leaders in northern Iraq said that the clashes in Aleppo call into question the ceasefire with Turkey. Similarly, Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the PKK, described the Syrian developments as “an attempt to sabotage the Peace and Democratic Society Process.”45

The January 30 agreement underscores the SDF’s defeat on the battlefield and closes the door on meaningful autonomy in northeastern Syria. This also introduces new uncertainties for Ankara’s domestic peace process with the PKK. If the peace process weakens or collapses, Ankara is likely to increase pressure on pro-Kurdish political actors. In that case, the DEM Party could again face legal and political crackdowns, as has occurred during earlier breakdowns in the peace process.

Some reports suggest that non-Syrian PKK fighters have quietly begun leaving Syria for Iraq.46 While the PKK’s presence in Syria has long been a concern for Turkey, officials in Ankara do not view a potential regrouping in Iraq as a relief. In this context, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan said in an interview on developments in northeastern Syria that Turkey welcomes the YPG’s withdrawal from non-Kurdish areas, but stressed that further steps are needed. He also underlined that the issue extends beyond Syria, noting that once the Syria phase is over, an Iraq phase will likely follow.47 The Iraqi government protested Fidan’s additional comments regarding its alleged inability to control sovereign territory in areas where the PKK operates.48

Ankara views developments in northern Syria through a security lens shaped by decades of conflict with the PKK. The PKK’s declaration that it had dissolved itself and laid down arms does not fundamentally change this picture.49 In practice, the organization has merely ended active hostilities with the Turkish armed forces. Its armed capacity remains intact, as do its affiliated organizations in Syria, Iraq, and Iran, along with its networks in Europe and elsewhere. Developments in Syria will therefore continue to shape Turkey’s regional foreign policy, which remains primarily driven by security considerations.

Haşim Tekineş

The Syrian civil war has had a major impact on relations between Turkey and the United States. Syria has created both areas of cooperation and sources of tension between the two countries. As interests and the regional balance of power shifted, the nature of the relationship also changed.

Viewed through the lens of the Syrian crisis, Turkish–American relations can be divided into three phases. In the first phase, from 2011 to 2014, relations improved around a shared objective: political change in Syria. Between 2014 and 2024, relations became increasingly strained as the two countries pursued diverging interests. Since the fall of Bashar al-Assad in December 2024, Ankara and Washington have focused on managing and resolving their disputes.

Benefits of a Shared Enemy: Assad

When the Arab Spring began, Turkish–American relations were already deteriorating, if not in open crisis.50 Ankara had experienced several diplomatic confrontations with Israel, which raised concerns in Washington and European capitals. An Israeli commando raid on a Turkish flotilla led both countries to withdraw their ambassadors. At the same time, Turkey maintained cordial relations with Hamas, which the United States designates as a terrorist organization.

Turkey’s improving ties with Middle Eastern countries (especially Iran and Syria) fueled debates51 about a possible shift in its foreign policy orientation from West to East.52 Most notably, Ankara’s vote against UN Security Council sanctions on Iran in 2010 generated deep anger and disappointment in Washington.53

The Syrian crisis, however, altered this trajectory.54 It reshaped Ankara’s interests. Before the Arab Spring, Turkey had invested in stable relations55 with existing regimes and largely acted as a status quo power.56 Following the fall of Zine el Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia, however, Ankara began to see its interests aligned with political change rather than stability.

In Washington, the spread of popular protests and revolutionary enthusiasm revived long-standing hopes of democratizing the Middle East. President Obama called on Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, Muammar Qaddafi in Libya, and Bashar al-Assad in Syria to step aside. He also authorized a military operation against Qaddafi’s forces in Libya.

These shifts in Ankara and Washington brought their interests closer together.57 President Obama viewed Erdoğan as a key regional partner. Following his “leading from behind” approach,58 Obama expected Turkey to play a central role in shaping regional change – as a Muslim-majority country with a democratic system.59 Although rarely stated explicitly, Turkey was at times seen as a potential model for the region.

Ankara, meanwhile, needed American military power. Turkey’s political and economic influence was growing, as were its ambitions, but it lacked sufficient hard power. Moreover, Erdoğan’s control over the military (which viewed armed involvement in Syria as highly risky) was still limited. As a result, the Turkish government depended on U.S. military leadership to advance proposals such as a safe zone or a no-fly zone.

This convergence created a positive atmosphere in Ankara–Washington relations.60 Leader-to-leader diplomacy intensified during this period. Most notably, Ankara approved the establishment of a NATO radar facility on its territory, part of a system aimed at Iran. At the same time, the CIA and Turkish intelligence cooperated in training and arming Syrian opposition groups fighting against Assad.61

As Assad managed to remain in power, however, the initial momentum in Turkish–American relations began to fade. The Turkish government’s crackdown on opposition protests in 2013, followed by corruption investigations later that year, raised questions about Ankara’s democratic credentials.62 In addition, Turkey’s support for radical jihadist groups in Syria increasingly alarmed Washington.63

Ankara expected64 Washington to assume greater responsibility.65 While the Obama administration used harsh rhetoric against Assad, it offered little support on the ground. Washington avoided direct military action against the regime. The CIA did not provide shoulder-fired anti-aircraft weapons that could have helped opposition forces defend themselves against regime air attacks. Although these developments strained bilateral relations, the real turning point came in the summer of 2014.

Diverging Interests

Radical groups operating in Syria had concerned the United States since 2012. Although Washington took some limited steps, these concerns did not lead to a major policy shift for some time. The fall of Mosul to ISIS fighters in June 2014, followed by the killing of American citizens, however, alarmed the Obama administration. Until then, the United States had been only partially committed to removing Assad. From June 2014 onward, defeating ISIS became Obama’s primary policy objective.66 This shift inevitably led to a divergence of interests with Ankara.

The Turkish government initially believed it could benefit67 from Washington’s growing urgency over ISIS. The United States needed a reliable partner on the ground, and Ankara assumed that its NATO ally would naturally fill this role. Turkey, however, demanded a broader strategy: the target should be not only ISIS but also what it saw as the root cause of the conflict—the Assad regime.

When Obama rejected this bargain, Erdoğan chose to drag his feet.68 He believed Turkey held strong leverage. The United States needed Turkish cooperation in the fight against ISIS, and the Incirlik air base was the closest major facility for air operations.69 Ankara, however, overplayed its hand. The Obama administration instead turned to another ground partner: the YPG, a Kurdish group affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which had been fighting the Turkish state for decades.70

The U.S.–YPG partnership caused deep anger and disappointment in Ankara.71 Although Turkey increased its own involvement in the fight against ISIS, this did not reverse Washington’s policy. U.S. forces armed, trained, equipped, and protected YPG fighters operating along Turkey’s border.

At the same time, Turkish–American relations faced additional crises, including the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, the detention of an American pastor, and Ankara’s purchase of Russian air defense systems. President Trump’s “don’t be stupid” letter marked a low point in the relationship. By then, the idea of a strategic partnership had largely collapsed. What remained was a narrow, transactional relationship.

Despite these tensions, Ankara and Washington gradually learned to manage their disagreements.72 U.S. officials sought to reassure Turkey by describing cooperation with the YPG as temporary and non-political. Under the Biden administration, leader-to-leader diplomacy weakened, but institutional channels improved. Still, the decisive shift in the relationship came only in December 2024.

Turkey’s Unexpected Victory

The fall of the Assad regime once again reshaped Turkish–American relations in Syria. For years, Ankara carved out areas of control in northern Syria. Its influence, however, depended on the rivalry between the United States and Russia. By playing these two powers against each other, Turkey sought to expand its room for maneuver. Even so, its influence remained limited and conditional. Assad’s forces and the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), led by the YPG, blocked Turkish advances to the west and east. Assad’s fall altered this balance by turning Turkey into the main external patron of the new Syrian regime. Under these new conditions, Washington and Ankara are likely to seek ways to manage and overcome their differences.

Turkey wants the new Syrian government, led by Ahmad al-Sharaa, to establish full control over the country. Ankara believes its interests align closely with al-Sharaa. There are significant opportunities for cooperation between Turkey and the new regime. Syria will need large-scale reconstruction, and Turkey is well positioned to play a major role in this process.

A strong, centralized Syrian state would also eliminate the possibility of a Kurdish statelet in northeastern Syria. For this reason, Ankara strongly supports the new regime’s efforts to assert authority over the entire country.

The United States has also established working relations with al-Sharaa’s government. Although doubts remain in Washington, al-Sharaa offers several advantages. First, he promises stability and a political reset. For fourteen years, Syria has been a source of conflict, terrorism, and displacement. If al-Sharaa succeeds in restoring order, this could help reduce regional tensions.

Second, al-Sharaa is well positioned to fight ISIS and contain other Islamist groups. Given his al-Qaeda background, his Islamist credentials are difficult to challenge. He founded Jabhat al-Nusra as al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate and survived the brutal conditions of the civil war. ISIS partly emerged from this organizational environment, and al-Sharaa later fought ISIS and rival Islamist groups for territorial control. After nearly fourteen years of conflict, he emerged victorious and entered Damascus. Few actors in Syria are better placed to combat ISIS and discipline other armed Islamist factions.

Al-Sharaa has also sought to present himself as a statesman. He appears open to compromise and political adaptation. Most strikingly, he has shown willingness to explore an agreement with Israel—an extraordinary step for a former al-Qaeda figure.

Syria has never been a top priority for the United States. President Trump appears particularly reluctant to become deeply involved in Middle Eastern conflicts. As long as Syria under al-Sharaa does not generate new crises, Washington is unlikely to care deeply about who governs from Damascus. After all, the United States withdrew from Afghanistan and left the Taliban in power only a few years ago.

So indeed, between its former ally Mazlum Abdi’s SDF and its long-standing adversary Ahmad al-Sharaa, Washington appeared to side with the latter during the clashes in January 2026. Backed by Ankara, Damascus suspended U.S.-led mediation talks with the SDF and launched military operations that resulted in the Syrian government gaining control over most of northern Syria.73 When a new ceasefire entered into force on February 2, the Syrian map had changed significantly. The Arab components of the SDF shifted their allegiance to Damascus, leaving the PKK-affiliated YPG increasingly isolated.

Beyond diplomatic contacts and efforts to facilitate a ceasefire, the United States did not take any military steps to protect its Kurdish partners.74 Isolated in a hostile regional environment, the YPG was ultimately compelled to accept Damascus’s full sovereignty and its integration into the Syrian military.

The new agreement, however, does not outline a clear pathway for the YPG’s integration into the new political order.75 The ambiguity of its language and the existing balance of power provide Damascus with a wide range of options, while leaving the YPG with limited leverage. As a result, the implementation of the agreement may not lead to meaningful integration in practice.

Nevertheless, regardless of how the agreement is implemented, Syria has shifted from an arena of conflict to one of cooperation between Turkey and the United States. Trump, who tends to view international politics as a division of spheres of influence among powerful actors, appears to see Syria as falling76 within Erdoğan’s domain.77 Although his interest in Syria has never been strong, he views Erdoğan as a partner with whom he can cooperate if necessary.

From Ankara’s perspective, Trump also represents a key partner in efforts to restrain Israel. Israel’s contacts with Damascus have so far produced a relatively constructive atmosphere of dialogue and compromise. Yet the highly volatile dynamics of the region could revive earlier hostilities. In such a scenario, Ankara would once again rely on Trump, given his influence over Tel Aviv.

The Syrian civil war has transformed Turkish–American relations from a brief period of strategic convergence into a long phase of tension, followed by a cautious form of cooperation. Initial alignment around regime change gave way to deep disagreements over priorities, partners, and methods, particularly after the rise of ISIS and the U.S. partnership with the YPG. The fall of the Assad regime in late 2024 marked a new turning point by reshaping the balance of power on the ground and redefining the interests of both Ankara and Washington. While fundamental differences remain, especially regarding governance and long-term regional stability, Syria has ceased to be a primary source of confrontation. Instead, it has become an area where Turkey and the United States pragmatically manage their interests, reflecting a broader shift from strategic partnership to transactional cooperation.

Servet Akman

The fall of the Assad regime in Syria has opened a new chapter in Turkish–Israeli relations. For a long time, the Assad regime was a major security concern for Turkey. For Israel, it was “the devil they knew.” Israel focused on containing the Assad regime and Iran’s proxies, while Turkey’s military presence in Syria remained a secondary issue. The overthrow of Assad has since complicated Israel’s security environment, along with Turkey’s increasingly active role in Syria.

From Managed Threat to Growing Uncertainty

Israel’s Syria policy has mainly been shaped by a threat perception emanating from Hezbollah and its backer, Iran. With the outbreak of the civil war, Tehran and its proxies expanded their activities in the region, and Syria increasingly served as a corridor for the transfer of weapons to Hezbollah in Lebanon. In this regard, Israel has adopted a strategy of fighting the enemy away from its borders and eliminating their capacity to retaliate. Therefore, over the years, Israel has entrenched itself along its northern border.

The defeat of Hezbollah, the killing of senior leaders including Hassan Nasrallah, and the ensuing 12-day war with Iran weakened—though did not entirely eliminate—the threat posed by Tehran and its proxies. With this menace reduced, Israel’s focus has shifted. For the Netanyahu government, the main concern is now the new government in Syria and the uncertainty it brings.

Competing Visions: A Unified Syria versus a Fragmented One

Israel’s policy in Syria focuses on preventing the emergence of a strong, unified state that could pose a security threat.79 This new Israeli strategy in Syria, which can be defined as containment,80 has led the IDF to conduct regular attacks. Over the past year, Israel has carried out more than 600 air, drone, and artillery strikes across Syria—nearly two attacks a day—according to data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED). Quneitra was the most heavily targeted area with at least 232 strikes, followed by Deraa with 167 attacks, while Damascus governorate was hit at least 77 times, including 20 strikes on the capital itself.81 Israel has also occupied further Syrian territories after the fall of the Assad regime.82

Turkey, however, strongly advocates for a stable and unified Syria, while helping to consolidate the new regime and forcing the Kurdish entity to become part of the central government. In the meantime, Turkey has ramped up its efforts to consolidate the new regime, integrate it into the international community and provide support in all fields to re-establish a functioning state.83 According to state-run Anadolu Agency, President Erdoğan has instructed the ministries to start the post-war reconstruction in coordination with the Syrian regime.84 Although Turkey has the capacity to realize these projects to some extent, it certainly needs financing from the international community.85 More importantly, these projects need a politically stable regime and security on the ground.

In this context, heated exchanges between Turkish and Israeli governments have grown increasingly confrontational. Turkey has been criticizing Israel’s strikes as destabilizing and fostering chaos, calling the international community to act against Israel’s operations in the region.86 Israel rejects Ankara’s accusations of destabilization and claims that Turkey wants to have a protectorate state in Syria.87 Therefore, some in Israel even started to view Turkey as the new Iran, considering its activities in Syria.88 More reasonable voices in Israel, however, acknowledge that Turkey is not Iran but a threat to Israel’s security.89

These diverging policies towards Syria have heightened the tension between Turkey and Israel.90 The exchange of loaded charges against each other paved the way for speculation about a direct confrontation between Turkey and Israel. Fearful of Turkey’s entrenchment in Syria after the fall of Assad, Israel basically obliterated Syria’s remaining military capabilities and destroyed the infrastructure that could be or were planned to be used by Turkey.91

While the Sharaa government is eager to work with Ankara, other groups in the country will welcome any kind of support from Israel. Relying on the U.S. as well as Israeli support, Syrian Democratic Forces have resisted the idea of integrating their forces with the new Syrian regime.92 In this regard, although Israel has so far avoided providing tangible support to a secessionist Kurdish movement, the developments in Syria today could make such support more likely in the future.

On the one hand, Israel could push the U.S. administration to obstruct both the Turkish government and the Syrian regime, to the detriment of efforts to consolidate authority in Damascus. On the other hand, relying on its air superiority and existing operational freedom in Syria, Israel may conduct critical operations targeting the Syrian regime to prevent any security entrenchment against its interests. Israel also feels unhindered in supporting the Druze community in southern Syria.93

The Gaza War and Hardening Positions

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict complicates matters for Turkey and Syria.94 Although Erdoğan has been pragmatic and successful in managing the public sentiment against Israel in the past, the situation in Gaza after 2023 has hardened the Turkish public against Israel. The erosion of trust, or should we say an unprecedented level of mistrust, between the parties has led Israel to reject Turkey’s participation in the Gaza Stabilization Force.95 Tensions around the Palestinians will deepen the mistrust and will have the capacity to render any de-escalation mechanisms in Syria meaningless.

Nonetheless, Israel’s ability to keep Turkey out of regional initiatives may be wearing thin, especially given President Donald Trump’s close relationship with President Erdoğan. Speaking alongside Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in December 2025, Trump highlighted his personal rapport with both leaders, saying, “I know Erdoğan very well and as you all know, he’s a good friend of mine.96 I believe him and I respect him. So does Netanyahu.” As one source quoted by The Jerusalem Post put it, “There is a limit to how many times Israel can say ‘no’ to Trump regarding President Erdoğan.”97 In this vein, the United States has facilitated direct talks between Israel and Syria. In January, senior Israeli and Syrian officials met in Paris and agreed to establish a joint communication cell to support intelligence coordination, military de-escalation, and diplomatic engagement under the supervision of the United States.98

Compared to Turkey’s more ambitious plans, Israel’s strategic objectives in Syria are easier to achieve. After all, building a new nation is far harder than fueling divisions in an already vulnerable country. Turkey and Israel have serious doubts about each other’s intentions. Yet, both sides are aware of the costs of such a direct confrontation. This has led them to engage in de-escalation talks, making a direct military clash less likely.

Overall, Syria is evolving into a geopolitical challenge for Israel and Turkey, with each pursuing conflicting agendas. These differences are hard to align and will remain a persistent source of tension between Turkey and Israel.

Mehmet Demirbaş

On the eve of the civil war, Syria was a lower-middle-income country with steady growth and relatively stable macroeconomic indicators. Between 2000 and 2010, real GDP grew by an average of 4.8 percent annually, inflation averaged 4.9 percent.100 Trade accounted for 64 percent of GDP, and GDP per capita stood at 2,731 dollars in 2010. Agriculture accounted for roughly 20–25 %of GDP, with the country largely self-sufficient in wheat, while industry contributed a significant share through textiles, food processing, chemicals, and construction materials.101 Tourism generated more than $6 billion a year from some 8.5 million tourists.102

Syria had developed economic relations with regional partners. Syria–Turkey Free Trade Agreement signed in 2004 aimed to progressively liberalize trade, enabling developing commercial and manufacturing linkages.103 The idea of a Gaziantep–Aleppo industrial corridor symbolized this integration, with complementarities between Turkish and Syrian firms in light manufacturing and logistics.

The outbreak of civil war in 2011 shattered this economic fabric. According to official statistics, Syria’s gross domestic product contracted by 53 percent between 2010 and 2022.104 By contrast, World Bank estimates based on nighttime light data, used as a proxy for economic activity, point to a much steeper decline of 84 percent between 2010 and 2023.105 Exports collapsed from more than $8,8 billion in 2010 to roughly $1.8 billion by 2021.106

The country’s official state budget fell sharply from 9 billion dollars in 2020 to 6.8 billion in 2021, 5.3 billion in 2022, and 3.6 billion dollars in 2023 at the official exchange rate.107 Syria’s evolution into a quasi-narco-state was closely linked to the regime’s economic collapse along with the civil war.108 Partly in response to economic contraction, the Assad regime increasingly relied on Captagon trafficking. This drug trafficking was reportedly generating approximately 5.7 billion dollars in 2021 alone, turning narcotics into Syria’s primary revenue stream.109

With the overthrow of the Assad regime in December 2024, Syria’s transitional authorities have confronted a deeply fragmented and damaged economy. The country’s GDP fell by around 1.5 percent in 2024, the continuation of a long contraction under wartime conditions, but modest growth near 1 percent is expected in 2025 according to the World Bank, signaling a very early phase of recovery.110

Syria’s new leadership has indicated a move toward a free-market economic model, marking a break from decades of tightly controlled state management.111 Proposed reforms focus on dismantling restrictive trade and customs systems within the country to attract investment and reconnect the economy with global markets.

Reconstruction Costs and Infrastructure Needs

The scale of physical damage of the civil war underscores the enormity of the task. The World Bank estimates that $216 billion will be required to rebuild infrastructure, housing, and economic assets destroyed during the conflict—nearly ten times Syria’s 2024 GDP.112 One of the largest needs are in electricity networks, transport corridors, and urban infrastructure in highly damaged areas such as Aleppo and the Damascus countryside.

Due to devastation of the civil war, the Assad regime could only supply electricity a few hours daily. At the end of 2025, thanks to new power plants and a steady gas supply from Turkey, the government in Syria has been able to provide reliable electricity to major cities, a development that is crucial for industrial revival.113

Oil was once a cornerstone of Syria’s export earnings and fiscal revenues. Prior to the civil war, production hovered in the 400,000 of barrels per day; by 2023, output had fallen to under 40,000 barrels per day.114 Rehabilitating oil and gas infrastructure in Syria could significantly bolster state revenues, reduce import dependence, and finance reconstruction.115 This will necessitate foreign capital, technology transfer, and stable governance agreements covering exploration rights and resource management.

Agriculture, historically accounting for a large share of GDP and employment, remains central to Syria’s economy. Before the war, Syria was mostly self-sufficient in wheat, a staple crop, and cultivated export crops such as cotton. And, Syria was producing up to four million tons of wheat in strong harvest years and exporting roughly one million tons of that output. However, recent droughts have reduced wheat production by nearly 40 percent in 2025 and resulted in deficit of 2.73 million metric tons according to the UN.116

Reviving agriculture requires repairing irrigation infrastructure, restoring landmine-contaminated fields, and rehabilitating supply chains.117 International assistance and partnerships will be critical to rebuild agricultural production and food security, and to re-establish Syria as a net exporter of selected commodities.

Sanctions and International Reintegration

Monetary institutions are central to economic recovery. Syria’s Central Bank under new leadership has embarked on ambitious reforms.118 Confidence-building steps include plans to redenominate the currency (removing zeros) to strengthen price stability and rebuild trust in the Syrian pound. At the same time, the bank is tightening fiscal financing practices, stabilizing monetary policy, and partnering with global financial services players to modernize payments. These moves lay foundational groundwork for renewed private credit and investment.

Despite early stabilization, trade remains far below pre-war levels. Exports that was $18.4 billion in 2010 have collapsed to low single-digit billions.119 According to data compiled by The Syria Report, trade between Syria and Turkey became significantly more imbalanced in 2025. Turkish exports to Syria rose to around $3.5 billion, up from approximately $2.2 billion in 2024, while Syrian exports to Turkey fell to roughly $235 million, down from about $435 million in 2024.120 This trend has raised concerns among Syrian industrial actors and may increase pressure on the country’s external balances.121

Reviving external trade also requires reducing barriers to cross-border commerce and full integration into global financial and payment systems, such as SWIFT. In this regard, international sanctions that isolated Syria for over a decade have been progressively eased in 2025.122 The U.S. Congress repealed the Caesar sanctions in December 2025. Introduced in 2019 to penalize the Syrian state for systematic human rights abuses, the Caesar sanctions had severely constrained Syria’s economy by limiting access to international finance and discouraging investment. The EU has also suspended restrictive measures, enabling engagement in trade and finance, though security-related restrictions remain.123

Syria’s post-war economic landscape is marked by immense reconstruction needs, deep human and physical losses. One year after the regime change, early signs of stabilization, such as modest growth prospects, Central Bank reforms, export recovery efforts, and international engagement provide cautious optimism.

For Turkey, keeping the Sharaa government in power in Syria is a priority. Turkey is backing this through practical steps, including facilitating trade measures, aid and housing projects, repairing infrastructure, providing military training, expanding counter-terrorism cooperation, and improving access to education and psychosocial support.124 Reinvigorating the Gaziantep–Aleppo corridor could also boost trade and investment inflows.

The path ahead requires sustained investment in energy, agriculture, and transport infrastructure. If these building blocks converge, alongside inclusive political agreements and effective use of diaspora networks, Syria’s economy can begin a gradual transition to recovery.

The government led by Ahmad al-Sharaa in Damascus is still operating in a fragile environment. State authority does not extend evenly across the country. In several regions, minority communities remain uncertain about the new leadership. These tensions have created openings for external military involvement, particularly by Israel and, to some extent, by Turkey.

The question of who governs Syria — and how the country is governed — has been one of the most critical foreign policy issues for Turkey, with direct implications for its domestic politics. From Ankara’s perspective, prolonged instability in Syria could weaken the new authorities and complicate efforts to stabilize the country. This approach has shaped Turkey’s posture since the collapse of the Assad system. Ankara moved quickly to recognize the new authorities and positioned itself as one of their key external partners.

There is a strong belief in Ankara that a political opening in a fragmented society could trigger renewed violence and weaken Sharaa’s authority. In this vein, Turkish policymakers have shown little interest in pushing for political liberalization in Syria. Its immediate focus has been on supporting institutions capable of controlling territory and maintaining internal order.

In this regard, eastern Syria remains the most sensitive issue for Turkey. The Syrian Democratic Forces lost much of their territorial and economic leverage after the fighting in early 2026. Still, the legacy of autonomous political and security structures continues to complicate reintegration under Damascus.

Economic recovery will be critical for the survival of the new political order. Syria’s infrastructure remains heavily damaged. Energy supply is inconsistent. Poverty remains widespread. Without visible improvements in daily life, the new authorities could face growing pressure from within. If reconstruction progresses, Syria’s recovery will likely become more closely linked to Turkish trade and energy networks.

Syria’s trajectory is unfolding within a broader regional and international landscape shaped by several major external actors. Turkey has become one of the most influential actors on the ground, but developments are also shaped by the policies of the United States, Israel and other Gulf countries.

Turkey can influence Syria’s direction but cannot determine it. The durability of Turkey’s position will ultimately depend on whether the new Syrian leadership can gradually rebuild state authority, restore economic functionality, and re-establish Syria as a functioning sovereign state.

End Notes

1- Craig Parsons, 2016. “Ideas and Power: Four Intersections and How to Show Them.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (3): 446–63, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13501763.2015.1115538 .

2- David Marsh, 2009. “Keeping Ideas in Their Place: In Praise of Thin Constructivism.” Australian Journal of Political Science 44 (4): 679–96. doi:10.1080/10361140903296578, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10361140903296578.

3- Parsons, “Ideas and Power,”

5- John M. Owen IV, The Clash of Ideas in World Politics: Transnational Networks, States, and Regime Change, 1510–2010 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691142395/the-clash-of-ideas-in-world-politics.

6- “Rabia Sign Now a Global Sign of Saying No to Injustice: PM Erdogan,” Anadolu Agency, November 3, 2013, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/archive/rabia-sign-now-a-global-sign-of-saying-no-to-injustice-pm-erdogan/206982.

7- “How Rabaa and Its Symbol Changed Turkish-Egyptian Relations,” Middle East Eye, August 14, 2022, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/rabaa-turkey-egypt-symbol-relations-changed.

8- Ragip Soylu, “Turkey Eyes Closer Egypt Ties with Crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood,” Middle East Eye, July 25, 2025, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-eyes-closer-egypt-ties-crackdown-muslim-brotherhood.

9- “Turkish Diplomatic Outreach Deepens Ties with Libya in 2025,” Daily Sabah, January 2, 2026, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/turkish-diplomatic-outreach-deepens-ties-with-libya-in-2025.

10- Mark Blyth, Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/great-transformations/870BE71687305B1E858E49FD3FDD578B.

11- İbrahim Kalın (@ikalin1), “Türkiye Ortadoğu’da yalnız kaldı iddiası doğru değil ama eğer bu bir eleştiri ise o zaman söylemek gerekir: Bu, değerli bir yalnızlıktır,” Twitter, August 7, 2013, https://x.com/ikalin1/status/362746057513385984.

12- “Erdoğan’dan ‘U’ Dönüşü: Geçiş Sürecinde Esed’le Gidilme Gibi Bir Şey Olabilir,” Cumhuriyet, September 24, 2015, https://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/haber/erdogandan-u-donusu-gecis-surecinde-esedle-gidilme-gibi-bir-sey-olabilir-375624.

13- An earlier version of this article was published by InstituDE on January 19, 2026 at https://www.institude.org/opinion/what-the-sdfs-miscalculations-meant-for-turkey-and-syria

14- Congressional Research Service, Syria: Transition and U.S. Policy, CRS Report RL33487 (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, September 5, 2025), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/RL33487.

15- Bethan McKernan, “Isis Defeated: US-Backed Syrian Democratic Forces Announce,” The Guardian, March 23, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/23/isis-defeated-us-backed-syrian-democratic-forces-announce.

16- “Syrian Army Captures Previous U.S. Base in Hasakah Province,” Xinhua, October 20, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-10/20/c_138486378.htm.

17- “Explainer: Kurdish Neighborhoods Besieged in Aleppo,” Rojava Information Center, December 3, 2024, https://rojavainformationcenter.org/2024/12/kurdish-neighborhoods-besieged-in-aleppo/.

18- Home Office, Syria: Country Policy and Information Notes, (London: UK Government, December 2024), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/syria-country-policy-and-information-notes.

19- Alex MacDonald, “Assad Forces Withdraw in Daraa and Deir Ezzor as Syrian Rebels Advance on Homs,” Middle East Eye, December 6, 2024, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/syria-assad-withdraw-daraa-deir-ezzor-rebel-homs.

20- Ece Toksabay and Jonathan Spicer, “Rebels Take Syrian City from U.S.-backed Group after U.S.-Turkey Deal, Source Says,” Reuters, December 9, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/rebels-take-north-syria-town-us-backed-group-turkish-source-says-2024-12-09/.

21- “Syrian Delegation Meets Israelis in Paris Amid Sovereignty Breaches,” Al Jazeera, January 5, 2026, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/1/5/syrian-delegation-meets-israelis-in-paris-amid-sovereignty-breaches.

22- Haşim Tekineş, “Syria’s Fate Still Hinges on Trump,” Institute for Diplomacy and Economy, February 9, 2026, https://www.institude.org/opinion/syrias-fate-still-hinges-on-trump.

23- Al Jazeera Staff, “Syrian Army Announces Full Control of Deir Hafer after SDF Withdrawal,” Al Jazeera, January 16, 2026, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/1/16/syrian-army-warns-of-strikes-against-kurdish-led-sdf-east-of-aleppo.

24- Tarek Chouiref, “Syrian Army Sends Reinforcements to Eastern Aleppo Amid Tensions with SDF,” Anadolu Agency, January 14, 2026, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/syrian-army-sends-reinforcements-to-eastern-aleppo-amid-tensions-with-sdf/3798990.

25- Naher Media (@nahermedia), “نهر ميديا ترصد دخول وحدات من الجيش السوري إلى مدينة دير الزور,” X, January 15, 2026, https://x.com/nahermedia/status/2011057470467174777.

26- Daily Sabah, January 16, 2026, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/war-on-terror/pkk-linked-senior-terrorist-from-n-iraq-in-syria-to-lead-sdf-attacks.

27- Tinshui Yeung, “Syrian Army Moves East of Aleppo after Kurdish Forces Withdraw,” BBC News, January 17, 2026, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ce3k279e53eo.

28- Rania Abushamala, “Syrian Army Announces Its Advance Toward Tabqa Military Airport West of Raqqa,” Anadolu Agency, January 17, 2026, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/syrian-army-announces-its-advance-toward-tabqa-military-airport-west-of-raqqa/3802382.

29- Asiye Latife Yilmaz, “US Calls on Syrian Army to Halt ‘Offensive Actions’ in Aleppo-Tabqa Areas,” Anadolu Agency, January 17, 2026, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/us-calls-on-syrian-army-to-halt-offensive-actions-in-aleppo-tabqa-areas/3802590.

30- Muhammed Semiz, Omer Koparan, Mehmet Nuri Ucar, and Serdar Dincel, “Syrian Tribes Largely Liberate Part of Deir ez-Zor Occupied by YPG/SDF Terrorists,” Anadolu Agency, January 18, 2026, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/syrian-tribes-largely-liberate-part-of-deir-ez-zor-occupied-by-ypg-sdf-terrorists/3802964.

31- Seth J. Frantzman, “Syria’s Government Faces Pivotal Moment against SDF, as It Retakes Largest Oil Field – Analysis,” Jerusalem Post, January 18, 2026, https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/article-883690.

32- Mehmet Demirbaş, “Syria’s Way Ahead: Prospects for a Ruined Economy,” Institute for Diplomacy and Economy, January 5, 2026, https://www.institude.org/opinion/syrias-way-ahead-prospects-for-a-ruined-economy.

33- “Terms of the Ceasefire and Integration Agreement between Syria and SDF,” SANA (Syrian Arab News Agency), January 18, 2026, https://sana.sy/en/syria/2291194/.

34- Ibrahim Hamidi, “How the US Got the SDF to Capitulate to Damascus,” Al Majalla, February 2, 2026, https://en.majalla.com/node/329476/documents-memoirs/how-us-got-sdf-capitulate-damascus.

35- “US to Lift Syria Sanctions to Give Country ‘a Chance at Peace,’ Says Trump,” France 24, May 13, 2025, https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20250513-us-to-lift-syria-sanctions-to-give-country-a-chance-at-peace-says-trump.

36- Rabia Iclal Turan and Serife Cetin, “US Envoy Says SDF Is YPG/PKK, Rules Out Separate SDF State in Syria,” Anadolu Agency, July 11, 2025, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/us-envoy-says-sdf-is-ypg-pkk-rules-out-separate-sdf-state-in-syria/3628638.

37- An earlier version of this article was published by instituDE on December 19, 2025 at https://www.institude.org/opinion/turkeys-security-approach-in-northern-syria

38- “SDF Disassociates Itself from the PKK Following Turkish Attacks,” Enab Baladi, October 31, 2024, https://english.enabbaladi.net/archives/2024/10/sdf-disassociates-itself-from-the-pkk-following-turkish-attacks/.

39- “Syrian Kurdish Groups Influenced by Jailed Militant Ocalan,” Reuters, February 27, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/syrian-kurdish-groups-influenced-by-jailed-militant-ocalan-2025-02-27/.

40- Mustafa Enes Esen, “The Legitimacy Issue in Turkey’s Military Interventions in Syria and Libya,” Institute for Diplomacy and Economy, February 17, 2021, https://www.institude.org/opinion/the-legitimacy-issue-in-turkeys-military-interventions-in-syria-and-libya.

41- “Türkiye’s Support to Syria Will Continue, Erdogan Tells al-Sharaa,” Daily Sabah, February 12, 2026, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/diplomacy/turkiyes-support-to-syria-will-continue-erdogan-tells-al-sharaa.

42- Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “No: 9, 18 Ocak 2026, Suriye'de Açıklanan Ateşkes ve Tam Entegrasyon Anlaşması Hk.,” January 18, 2026, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_-9_-suriye-de-aciklanan-ateskes-ve-tam-entegrasyon-anlasmasi-hk.tr.mfa.

43- Mustafa Enes Esen, “Turkey’s Security Approach in Northern Syria,” Institute for Diplomacy and Economy, December 19, 2025, https://www.institude.org/opinion/turkeys-security-approach-in-northern-syria.

44- Ömer Güler, Mustafa Enes Esen, and Ahmet Kalafat, “PKK’nın Kendini Feshetmesinin Sonuçlarına Dair Uzmanlarımızın Görüşleri,” Institute for Diplomacy and Economy, May 13, 2025, https://www.institude.org/opinion/pkknin-kendini-feshetmesinin-sonuclarina-dair-uzmanlarimizin-gorusleri.

45- Halkların Eşitlik ve Demokrasi Partisi (DEM Parti), “DEM Parti İmralı Heyetinin açıklaması,” January 18, 2026, https://www.demparti.org.tr/tr/basina-ve-kamuoyuna/22478/.

46-Ibrahim Hamidi, “Back to Qandil: PKK Fighters Finally Leaving Syria,” Al Majalla, February 12, 2026, https://en.majalla.com/node/329626/politics/back-qandil-pkk-fighters-finally-leaving-syria.

47- “Hakan Fidan'dan kritik mesaj: YPG'nin tarihi dönüşüm yaşaması gerekiyor; Suriye ayağı bittikten sonra Irak ayağı da var!” T24, February 9, 2026, https://t24.com.tr/haber/hakan-fidandan-suriye-mesaji-ypgnin-kurt-nufusunun-yasadigi-yerde-pozisyon-almasi-bir-onceki-haritaya-gore-cok-daha-saglikli-tarihi-bir-donusum-yasamasi-gerekiyor,1298047.

48- Dana Taib Menmy, “Iraq Protests Turkish FM's Remarks on PKK, Summons Back Ankara's Envoy,” The New Arab, February 12, 2026, https://www.newarab.com/news/iraq-protests-turkishs-fm-over-pkk-remarks.

49- Orla Guerin and Gabriela Pomeroy, “Kurdish group PKK says it is laying down arms and disbanding,” BBC News, May 13, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/czel3ry9x1do.

50- Soli Ozel, “Indispensable Even When Unreliable: An Anatomy of Turkish-American Relations,” International Journal 67, no. 1 (Winter 2011–12): 53–64, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23265965

51- Kemal Koprulu, “Paradigm Shift in Turkey's Foreign Policy,” The Brown Journal of World Affairs 16, no. 1 (Fall/Winter 2009): https://www.jstor.org/stable/24590749

52- Christopher Phillips, Turkey's Global Strategy: Turkey and Syria, edited by Nicholas Kitchen, LSE IDEAS Special Reports, SR007 (London: LSE IDEAS, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2011), http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/43498/.

53- UN Security Council, Resolution 1929, S/RES/1929 (June 9, 2010), https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un-documents/document/iran-sres-1929.php.